Website security is important. We all know it. For many though, it’s a topic they prefer not to talk or think too much about. They don’t really consider it in very many areas as they build or manage their site. Why?

Security is Scary

You know you want to be secure, so you start to check out this weird security thing. Brute force? You can handle that; good passwords, limit login attempts, maybe even two factor authentication. Then you suddenly become aware of cross-site scripting (XSS), SQL injection (SQLi), cross-site request forgery (CSRF), remote code execution (RCE), and potentially so many more that you’re simply terrified. You begin to buy into “ignorance is bliss”. But website security doesn’t have to be scary.

Security is Something You Can Handle

When you start to research website security it’s easy to become overwhelmed as you’re slowly exposed to all the various forms of attacks. Each can be nuanced, complex, and confusing. The good news is, you don’t need to know how every vulnerability works in order to increase your security. Many of them can be prevented by following some relatively simple best practices. With a little added effort and by making a few smart decisions along the way, you can drastically increase your online security.

When most people think about securing their site, the first thing they think of is their password. And passwords are important. They aren’t where you should start though.

Security and Your Host

The security of your site needs to be managed all the way down “the stack”. The stack is all the software that sits on top of each other in layers to become your website. The tip of this is likely all you really interact with – WordPress and your plugins. Below that is your database, PHP, caching tools, web server software like Apache or nGinx, and an operating system. There’s probably also a firewall somewhere either inside that stack or outside as a separate appliance.

Every part of this software stack needs to be properly configured, managed, and continually kept up to date. It’s integral to the security of your website. It’s also a lot of work and quite complex. Thankfully, you don’t have to worry about it if you choose a good quality host and let them worry about it for you.

Consider security when you choose a host. If you haven’t checked to see that your host has good security practices, take the time to do so. If you haven’t yet chosen a host, make sure that security is one of the things you evaluate when you do.

Choose Quality Software

Most of you are here because you use WordPress. I’m obviously biased, but I think that was a good decision for security. The WordPress security team works very hard to make sure that WordPress is as secure as possible. However, WordPress isn’t the only software you’re using to run your site.

You need to make good decisions about what plugins and themes you use as well. Did you consider security as you selected your plugins and themes? Did you look into the security practices of the companies or developers behind them? Don’t expect to find plugins or themes that have never had a security issue, but do look for those that have handled them well and have implemented good security practices into their development processes. You want quality plugins and themes with reputable people or companies that stand behind them.

Take the time to consider other software you’re using as well. Are you using a reliable and reputable SFTP client? Are you running good virus protection software on your computer? With the pervasiveness of the Internet, many modern computer viruses work to harvest login details from websites and send them to someone for later use. Learning to think about security at every step of the way, getting into the “security mindset”, will really help. You’ll start to see places that you can increase your security that you had never before realized even affected your website.

Great Password Practices

Everyone knows that it’s important to have good passwords, but what makes a password good? A good password is long, random, and unique.

How long should a good password be? I tell most people that it should be a minimum of twenty characters. All of mine are at least fifty unless the site or service has a lower limit (which usually leads to me whining lots and often reaching out to them to discuss better password practices).

What do I mean by random? Well…I mean random. Not a snippet from a poem you like, not a favorite verse, not a seemingly random combination of things you know or easily remember, and not a pattern on the keyboard. The best passwords are completely randomly generated.

Unique means that the password is only used in one place. The password to log in to my website is different from the one for my E-Mail, which is different from the one for my computer, which is different from the one for my back, etc, etc. I don’t use the same password in two places and neither should you.

How can I possibly have that many different fifty character passwords that are completely randomly generated? Do I have a super human mind? Not at all. I use a password manager. You can’t have good password practices without a password manager. I use LastPass. Lots of people love 1Password and it’s a great option as well. I don’t care which you use, but you need to use one.

This is one of those areas where you have to put in that added effort I mentioned. A password manager will take some time and effort to set up and get used to using. Eventually though, you’ll probably find that it makes things easier not harder. It’s a fantastic investment into your online security.

Two Factor Authentication

When you try to log into your site you fill in a username field. On this site for me, that’s either my E-Mail address or “aaroncampbell”. That’s me saying “I’m Aaron”. My site wants proof of that though, as it should. There are three basic ways you can prove you are who you claim to be.

- Something you know – A password for example. With your bank this might be a PIN. As a kid with a fort, it was a code word.

- Something you have – For your car, house, hotel room, etc this would be your key. “Let me in if I have this.” For your website this is probably your smartphone with an app on it.

- Something you are – Many phones are starting to support fingerprint access for example. Some data centers use retina scans.

Two factor authentication (2FA) simply means that in order to verify you are who you claim to be you must supply proof from at least two of these groups. For websites this is almost always something that you know – your password, and something that you have – your phone with an authentication app on it. I use Authy because I think it’s the most user friendly. It allows me to rearrange things to fit my preferences, add it to multiple devices, and even backup and restore everything for when I change devices. You can also use Google Authenticator or LastPass Authenticator.

There are two plugins that make easy to add 2FA to your WordPress website.

- iThemes Security Pro is a paid plugin that also does many other great things for your site. If you want to invest a little money in the security of your site, invest in your host and in this plugin.

- Two Factor is a free plugin by George Stephanis that adds two factor authentication to your site simply and effectively.

Like your password manager, some additional effort is required for setup and to get used to it. However, the added effort here will continue forever. Every time you log into a site you use two factor authentication on, it will take you an additional fifteen to thirty seconds. It is absolutely worth it though. Using multiple factors for identity verification increases security so much that it’s honestly hard to quantify.

Bonus: Once you get used to using two factor on your WordPress website, start using it everywhere else too. I use it on GMail, Github, Slack, Amazon AWS, Mailchimp, Mandrill and more!

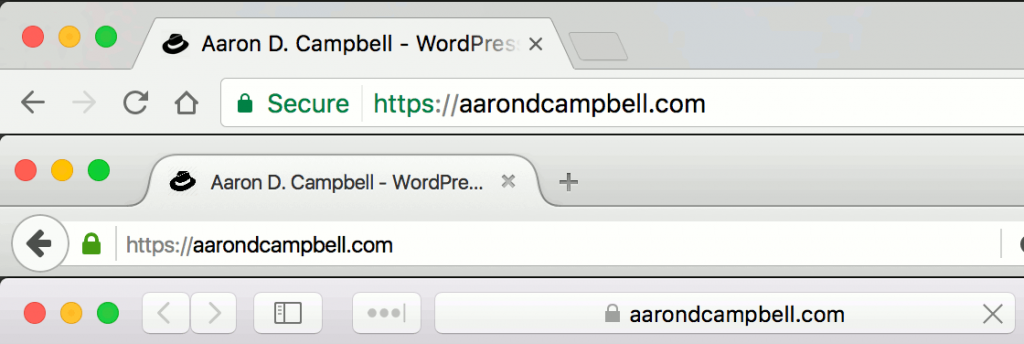

SSL Certificates

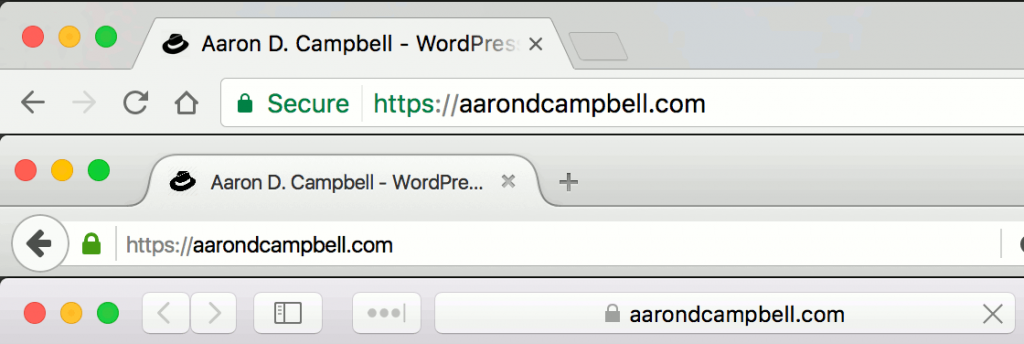

Encrypt all data sent between your website and the computer or device that’s accessing it with an SSL certificate. It’s the thing that changes the URL from http:// to https:// and adds a lock and/or a green color to the URL bar of the browser to let the user know they are browsing safely.

At this point, there’s no reason for any site to not have an SSL certificate. They used to be quite expensive but cost is no longer an excuse. Many hosts offer them for free and the ones that don’t offer them cheaply. Often you can install them yourself through your control panel, but if you can’t opening a ticket with your host should take care of it.

Is Security Really That Important?

People want to know “why would anyone want to attack my website?” They think that because they don’t process credit cards or store personal information, that no one would care to hack into their site.

It’s not if you get attacked, but rather how you prevent it from being successful.

There are two basic types of attacks that try to compromise sites.

Targeted attacks are the kind that people tend to think of first. A person or persons work to compromise a specific site for some sort of payout. Often they’re trying to get credit card numbers, identities, etc. They want a good payout and put in a concerted effort to get it.

The second, and far more prevalent, are scripted attacks. Programs written to crawl the internet and try to compromise sites. Pushing for sheer numbers they look for simple to break passwords, out of date software with vulnerabilities, and other known weaknesses that can be exploited in an automated way. Instead of a large payout from one targeted site, the script attacks hundreds of thousands or millions of sites, compromises thousands, and makes a little bit from each. These attacks aren’t only more prevalent, but are indiscriminate. Anything attached to the internet will be attacked. It’s not if, but when.

Make it Hard on Them

Attacks on your site will happen. You can drastically improve your security, and thus your ability to fend off these attacks, by following these best practices. They’re not overwhelming. They are all things you can do.

- Use a Security Conscientious Host – Keeping the stack your site is built on secure helps keep your site secure.

- Choose Quality Software – Starting with WordPress is great, but also look at your plugins and themes as well as software on the computers you use to build or access your site.

- Use Great Passwords – Great passwords are long, random, and unique. You can only do this correctly with a password manager.

- Use Two Factor Authentication – Two factor authentication will use something you know (password) as well as something you have (your smartphone) to verify you are who you claim to be. This is a massive leap forward in the security of your user account.

- SSL – Every site should have an SSL certificate. Inexpensive or even free, SSL certificates encrypt all data sent between your website and the computer or device accessing it.